IPTables is essentially the built in command-line tool for managing Netfilter hooks which basically manages firewall rules. IPTables interacts with the netfilter framework to filter through packets. Every incoming or outgoing network packet traversing the networking system will trigger the hooks on netfilter allowing programs that register with these hooks to interact with the traffic and to check that the packets conform to the existing firewall rules.

IPTables isn’t the only tool available for interacting with the netfilter framework. UFW (Uncomplcated firewall), firewalld and nftables can all interact with the netfilter framework to provide firewall functionality.

IPTables are really versatile. They are able to:

- Filter through IPv4 and IPv6 packets

- Both network and port translation (NAT/NAPT)

- Implement transparent proxies with NAT which becomes especially useful for port redirection.

- Packet manipulation (mangling) by altering the Type of Service, DSCP fields or the ECN flag.

Basic Structure

iptables is made up of some basic structures which are ‘layered’. IPTables use:

- Tables

- Chains

- Rules with Targets

With IPTables, multiple TABLES can be defined. Each table contains various chains and a chain is basically a set of rules. Rules define what happens to a packet. If a packet matches the rule, it goes to the specified TARGET. If the criteria is not matched, it moves on to the next rule. Every packet moves through the ruleset until it is either accepted, dropped or moved elsewhere.

Tables

IPTables provides 5 key tables each representing a distinct set of rules, organized by area of concern, for evaluating packets. For example, if a rule deals with packet filtering, it will be put into the filter table. If it deals with packet manipulation, it will belong to the Mangle table. Any table can call itself and it also can execute its own rules, which enables possibilities for additional processing and iteration.

IPTables are based on the netfilter modules i.e

- the

iptable_rawmodule which then becomes the Raw table is responsible for filtering packets before they reach more memory demanding operations. - the

iptable_manglemodule becomes the Mangle table is responsible for modifying the packet by altering the IP headers. - the

iptable_natmodule becomes the Nat table. It registers 2 hooks, the DNAT (Destination NAT) which transforms the packet before it’s pushed to the filter hook and the SNAT (Source NAT) which modifies the packet after it’s been through the filter hook. The NAT table fucntions as a configuration database and no packet filtering occurs. - the

iptable_filtermodule becomes the Filter table and thie table responsible for all the firewall functionality. - the

security_filtermodule becomes the Security table and thie table responsible for rules that manage access i.e Mandatory Access Controls(MAC) and Discretionary Access Controls(DAC) which are implemented by SELinux.

Chains

Each of the 5 tables has its own predefined chains. Tables are defined by general purpose, while chains determine when rules will be evaluated. Just like tables, chains mirror the names of the netfilter hooks they are associated with. These chain titles help describe the origin in the Netfilter stack. There are 5 chains.

- the PREROUTING chain is triggered by the

NF_IP_PRE_ROUTINGhook immediately upon packet reception. - the INPUT chain is triggered by the

NF_IP_LOCAL_INhook once the packet is moved to a local process. - the FORWARD chain is triggered by the

NF_IP_FORWARDhook once the packet forwarded through another interface. - the OUTPUT chain is triggered by the

NF_IP_LOCAL_OUThook once the packet is locally created. - the POSTROUTING chain is triggered by the

NF_IP_POST_ROUTINGhook once a packet is meant to be sent out.

Each table has it’s own chains. The table below shows how the 5 chains are distributed in the 5 tables. The NAT table has been split into two becasue it processes packets before and after they pass through the filter table.

| PREROUTING | INPUT | FORWARD | OUTPUT | POSTROUTING | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw | YES | - | - | YES | - |

| Mangle | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| NAT(DNAT) | YES | - | - | YES | - |

| Filter | - | YES | YES | YES | - |

| Security | - | YES | YES | YES | - |

| NAT(SNAT) | - | YES | - | - | YES |

Now that the raw table has 3 chains, how does a packet traverse that table into the next (mangle) table? Assuming that the server knows how to route a packet and that the firewall rules permit its transmission, the following flows represent the paths that will be traversed in different situations:

- Incoming packets destined for the local system: PREROUTING -> INPUT

- Incoming packets destined to another host: PREROUTING -> FORWARD -> POSTROUTING

- Locally generated packets: OUTPUT -> POSTROUTING

Understanding how packets move through the IPtable will be especially important when we look at how Docker and Kubernetes interact with IPTables.

This is a very high level breakdown of how a packet would traverse the IPTable if all the tables and chains were present. For an indepth graphical analysis, I’d recommend one on Wikipedia.

![[traversal.png]](/assets/img/traversal.png)

It can get really complicated to follow through with a packet but to see this in action, I’d advise to try out this script.

Copy the contents of that file into a shell script e.g test-iptables.sh

1

nano test-iptables.sh

Make the file executable then run it.

1

2

chmod +x test-iptables.sh

sudo ./test-iptables.sh

Here, you can confirm the contents of your local IPTables.

1

sudo iptables-save

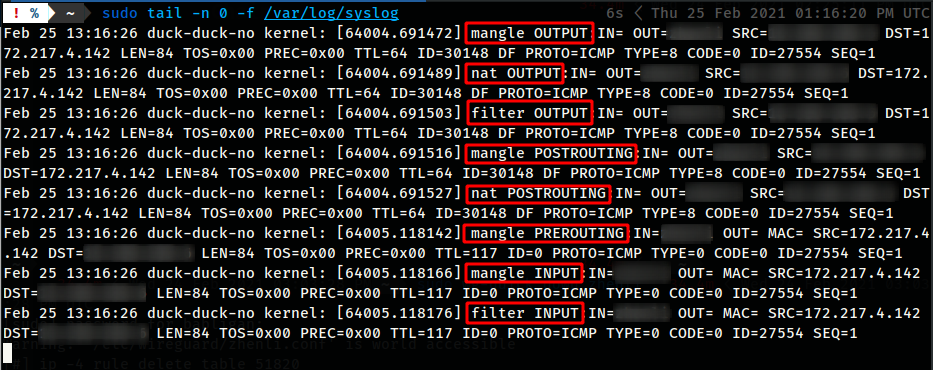

If all is well, run a simple ping on one tab on your terminal.

1

ping -c 1 google.com

On another tab, read the logs to see the packet traversal.

1

sudo tail -n 0 -f /var/log/syslog

In the end you should have something like this:

Using the flowchart, try and figure out what’s going on. Remember that a ping consists of an echo-request and an echo-reply.

Remember to flush your iptables using this script.

Just like before, copy the contents into a shell script. Make it executable and execute the file. Confirm that your IPtable is back to it’s default setting.

1

2

3

nano flush-iptables.sh

chmod +x flush-iptables.sh

sudo ./flush-iptables.sh

Rules

Chains are a series of rules that define how the packets are handled. Rules are defined as a set of matches and a target. Rules are followed by order until a match is found. If a match is found it goes to the rules specified in the TARGET or executes the special values mentioned in the rule. If the criteria is not matched, it moves on to the next rule all through the chain.

Matches

A match is the criteria or condition that has to be met before a packet is handled. The conditions can be defined by the source of the packet, the destination of the packet, the protocol used by the packet and even the interface via which a packet is received or through which it is to be sent out.

For example, a rule like:

1

iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --dport 25 -j ACCEPT

This rule matches/accepts all incoming SMTP (port 25) packets.

Targets

Targets are basically chains that determine what happens once a packet matches a rule. They are specified by the -j (–jump) switch i.e jump to TARGET. We could for example, DROP or ACCEPT a packet.

There are several targets available:

- ACCEPT - accepts the packet for processing.

- DROP - packet is dropped.

- RETURN - causes the packet to stop moving through the chain.

- REJECT - acts just like DROP but sends a response back to the sender.

- DNAT - only present in the PREROUTING and UOTPUT chains in the NAT table.

- SNAT - present in the POSTROUTING chain of the Nat table.

- MASQUERADE - similar to SNAT but does not require

--to-sourceas it’s made to work with IPs assigned dynamically.

Modifying the IPTable

To create rules you have to have sudo permissions. Usually a good starting point is to list out all the current rules that are configured. To do so, there are several commands:

1

2

3

4

5

iptables -L

iptables -S

iptables-save

#This only works if you've saved a previous configuration before.

cat /etc/iptables/rules.v4

A default installation of IPTables should have the INPUT, OUTPUT and FORWARD chains set to ACCEPT and no other rules present.

![[default-ruleset.png]](/assets/img/default-ruleset.png)

To edit a rule, the primary switches are -A which appends a new rule and -D which deletes a rule. You can also replace a rule using -R. To get more switches use the manpages.

Appending adds a rule to the end of the INPUT chain and uses the -A switch.

1

iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --dport 80 -j ACCEPT

To delete a rule, you must know its position on the chain. Deleting uses the -D switch.

1

iptables -D INPUT 1

This will delete the very first rule on the table.

You can create a rule at any position on the table using the insert switch. Inserting uses the -I switch.

1

iptables -I INPUT 4 -p tcp --dport 443 -j DROP

This will insert it as the 4th rule on the INPUT chain.

You can also replace rules in the chain using the -R switch.

1

iptables -R INPUT 4 -p tcp -s 172.16.10.0/24 --dport 80 -j ACCEPT

This rule will replace the rule on the 4th line.

To clear the iptables, use the -F switch. If no chain is specified, then all chains are flushed. Be cautious when flushing the table. If for example the INPUT policy is DROP or REJECT and the rules are flushed, all incoming traffic will be dropped or rejected and network communication broken. So before you flush your ruleset, ensure your INPUT chain has an ACCEPT policy.

1

iptables -F

By default, the rules added to the iptables are ephemeral, which means that everytime you reboot, your rules are gone. We need to install the netfilter-package to save our rules and make them persistent even after reboots.

1

2

3

4

5

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt install netfilter-persistent -y

#To save your configurations

sudo service netfilter-persistent save

sudo service netfilter-persistent restart

Resources: If you want to learn more about setting up a simple (or complex) firewall, I’d recommend the following sites.

I hope this blog answer some of the questions you might have had!